Planned obsolescence can be justified by arguing that products are replaced after a certain lifespan anyway. The components of a product would be manufactured precisely to be functional over the expected lifespan of the product.

This sounds reasonable. What’s the point in investing time and energy into supporting products that nobody uses. If products are designed to last exactly as long as they have to, consumers will get the most affordable products.

Who decides the lifespan of the products? Why do consumers replace their products? Are products replaced because users desire new products or because they have no choice due to obsolescence? When obsolete, would consumers replace the product even if it was still functional?

The answer depends on the type of product. There are products that are perishable, consumable or naturally wear (food, laundry detergent…) and are expected to be used within a certain timespan. Then there are products that could technically last forever and where user expectations don’t change much because technology has reached a point where the user experience does’t increase (a shovel, a chair).

The category of products I would like to discuss is a third category, and includes products like cars, cell phones or TVs – areas where there there has been historical technological advancement that made older products obsolete since consumer expectations have changed. In this category, it is assumed that there is perpetual technological advancement and therefore, consumers will have the desire to replace their products within a predictable timespan.

The issue with this is the following: If the only metric for how long products should be used is how long they’re commonly used, we won’t be able to make longer-lasting products. This is a self-fulfilling prophecy. When a product is designed to be obsolete after 5 years, the median consumer will likely replace it after 5 years. Then, the statistics will say “most users only use the product for 5 years.” When developing the next product, we’ll then look at the statistics and design it to only last 5 years. Let’s look at another example to understand how absurd this is.

In the early 90s, PC manufacturers shipped personal computers with 1 MB of RAM. Being limited to 1 MB of RAM, users obviously only used 1 MB of RAM. This could have stopped there. PC manufacturers could have done their statistics and say “our surveys have shown that users only use 1 MB of RAM so let’s ship the next generation of PCs with 1 MB of RAM as well.” This company would have gone out of business. No computers with 2 MB of RAM would have been made because there was never any data that users actually used it.

This hasn’t happened. Because computers constantly improved, PCs now have gigabytes of RAM. This is great. So great that in the last decade or so, it hasn’t really mattered. 16 GB of RAM are plenty for a normal user and the advancement of CPUs has slowed down. This means, we could use our computers longer, right?

Regarding obsolescence, however, nothing has changed.

To reduce waste, protect the environment and put more resources into actually improving our lives rather than maintaining the living standard, we must find a way to make products last longer and that starts with considering how long products could be used and not how long they’re used because of the planned obsolescence we already have.

We must stop the practice of planned obsolescence and build products that last longer, not shorter. Just like testing if users might use more RAM, we need to test if users will use products longer if the products last longer.

Let’s look at the automotive industry. Modern cars are more reliable and this has shown in the statistics. The average car is getting older which is a good thing, because that means less production of new cars is required and consumers can save money. The idea that a company needs to produce more to constantly grow is not sustainable. Besides creating virtual shareholder value, constantly producing new products to replace old products that could still be running doesn’t improve our living standard. If a car lasts 10 years and owners replace their cars after 10 years, they still only have a car. If the average car lasts 20 years, only half the cars need to be produced, which means that everyone still has a car, but half the resources are used to maintain that. The only sensible thing to do is to incentivize the creation of long-lasting products because perpetual replacement doesn’t actually create any value.

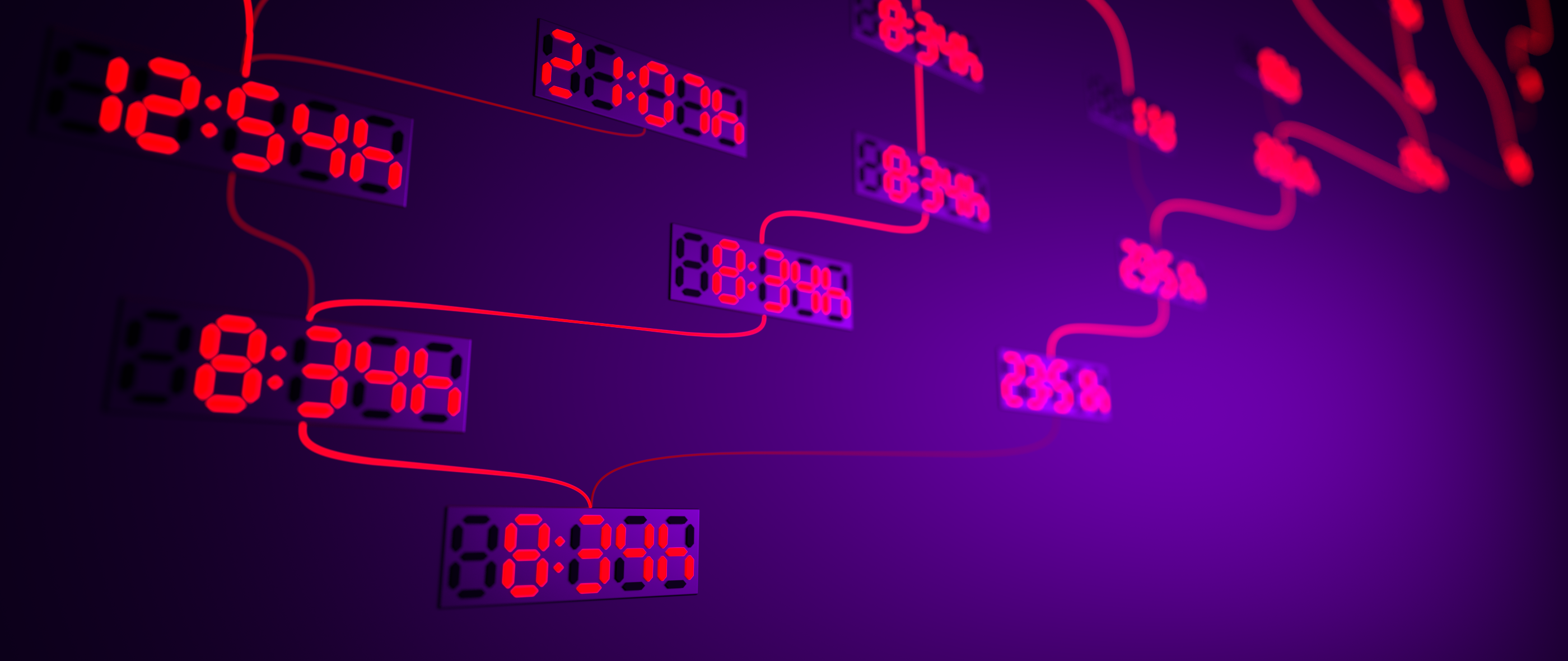

But then, what happened with consumer electronics? Why do we solder wearing parts (like SSDs) onto mainboards, giving our consumer electronics a predictable death clock, while still allowing car parts (like tires) to be replaced using common standards? Electronic products used to last longer as well, with electronics from the 80s still functional while 10 year old laptops might already be broken because their SSDs were soldered in.

While there was a lot of development in computers up until the early 2000s everything has slowed down. A decent, 2011 computer should still be pretty usable in 2021, whereas a 1990 computer was outdated in 1995.

Of course, modern consumer electronics got so complex that simple, accessible slots would’t be an option anymore if we want to have the small and lightweight devices we have today. But that doesn’t mean that designers and engineers cannot attempt to increase the usable lifespan of products instead of tying to do the opposite and precisely engineering devices to meet their doom when the “obsolescence” clock has reached the lifespan that has been determined to be a reasonable replacement time according to consumer behavior that is based on consumers wanting to replace their device in the past, with a lack of evidence that they still want to replace it (as opposed to being forced to replace it because they have no choice).

While society and the environment benefits from having to replace products less often, are governments actually willing to push for that change? If cars last 10 years, sales taxes for cars will be collected every 10 years per driver, whereas if cars last 20 years, sales taxes can only be collected every 20 years.

Companies that make the products also benefit from shorter lifespans because they can sell “upgrades” more often. It used to be that companies that made long-lasting products had a good reputation and therefore were able to sell more or higher priced products. But with the quickly changing consumer preferences today, I think this is becoming less of a factor when consumers make a purchase decision. How can you even know if a product will last or 10 years if it’s only been out for a couple of years and the company that makes it is some new startup that might not even exist by the time you consider replacing it?

How can we steer the economy in a way that companies can profit from creating reliable, long-lasting products?

Leave a Reply